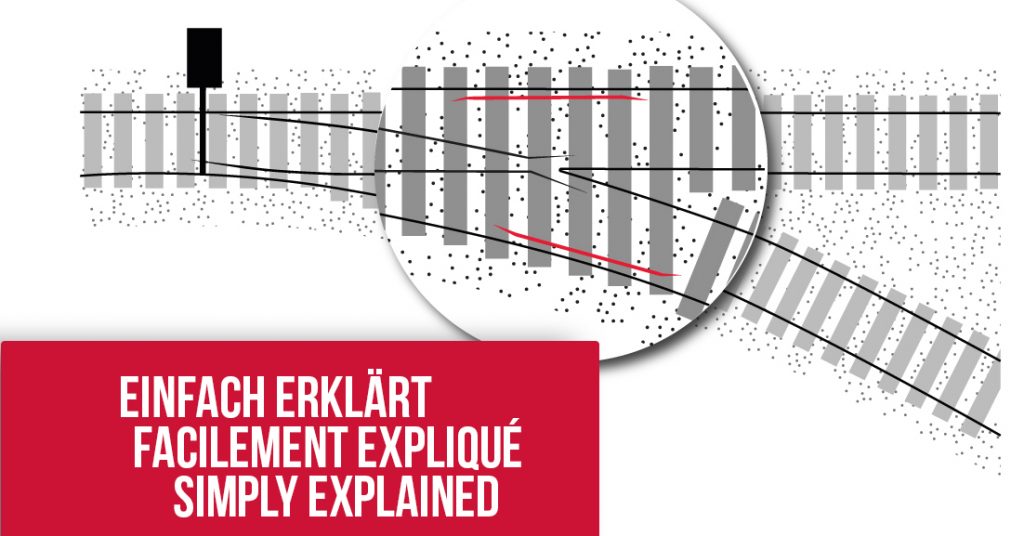

Simply explained : switches

Switches and crossings are among the basic building blocks of the railway infrastructure. The turnouts are controlled by the dispatchers in the signal boxes, which, thanks to these elements, can use the existing tracks as flexibly and efficiently as possible. With the help of switches, the train transitions from one to track to another can be done without interruption of travel. There are a variety of different types of turnouts. The selection of the switch depends on different factors, such as, for example, the number of existing tracks or the pass speed of trains on the affected track segment. In slower parts of the track, for example in train stations, trains can travel rather narrow curves. As a result switches can be designed in a more compact way. Turnouts in high-speed sections, however, have to be designed longer (up to 65 meters in Luxembourg) to enable safe track changes despite high speeds.

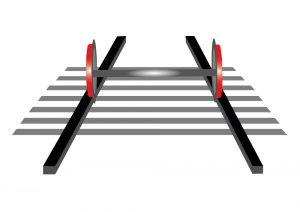

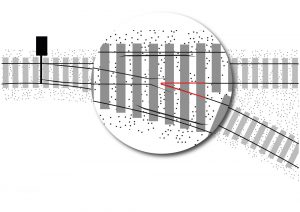

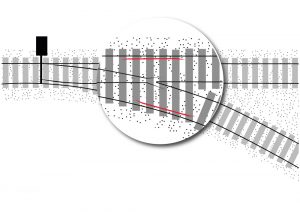

- During the journey, only the running surface of the wheels sits on the rail head.

- The wheel flange, the extended inner part of the wheel, does normally not come into contact with the rail. Its function is to guide the rolling stock in turnouts and crossings.

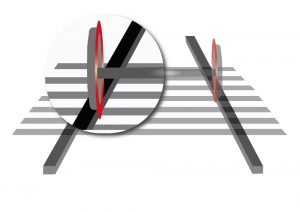

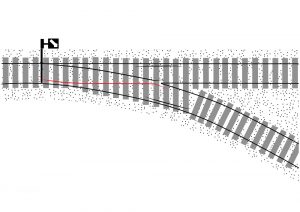

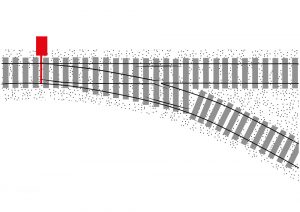

- The moving part of a switch consists of two interconnected switch blades.

- Together with the wheel flange one of these moving blades leads the rolling stock and sits tightly against the stock rail…

- … the other blade gives enough room for the wheel flange to pass through cleanly. The direction is thus set by the guidance of the wheel flange alongside the stock rail.

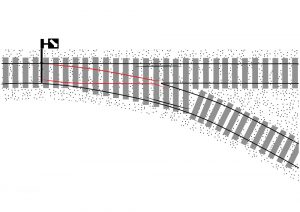

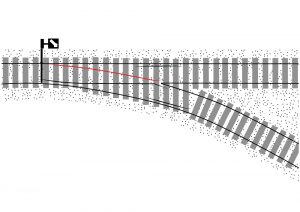

- In most cases switches are controlled by switch motors operated by dispatchers inside signal boxes.

- The different rail segments merge into the switch frog, particularly exposed to high stresses.

- Check rails provide additional security for track changes.